I received this book for free from in exchange for an honest review. This does not affect my opinion of the book or the content of my review.

Doomsday Book

It is part of the Oxford Time Travel #1 series and is a in Paperback edition that was published by Bantam Spectra on July 1992 and has 592 pages.

Explore it on Goodreads or Amazon

First in the Oxford Time Travel science fiction fantasy set in Oxford in 2054 and the fourteenth century where illness strikes everywhere.

Doomsday Book has won lots of awards: Hugo Award for Best Novel (1993), Nebula Award for Best Novel (1992), Locus Award for Best Science Fiction Novel (1993), Mythopoeic Fantasy Award Nominee for Adult Literature (1993), and Kurd-Laßwitz-Preis for Foreign Novel (1994).

My Take

I do love how well Willis portrayed the politics and feel of the people working for the college.

There were a few irritations: dropping us into the story and spouting off all sorts of technicalities without giving us a clue, the can’t-spit-out-all-the-info trope (I really hate this one, drives me mad), and the initial confusion of all the back-and-forth at the start [for me] as to what was past events and what was current events as Kivrin is getting ready to blast off and Dunworthy is thinking back over the argument of her going/not going. It’s what dropped everything from a “5” to a “4”. Other than that? It was brilliant.

I will give Willis credit for ratcheting up the tension with the confusion.

Willis explained once what a fix was. Once. With all this technical talk, I’d have appreciated her reinforcing its definition a few times along the way.

I loved the combination of history and science and medicine. The anthropological aspect of it. Kivrin had such a passion and reasons for going to fourteenth century England; I’d’a jumped with her!

Why title this Doomsday Book? Why not keep in line with Kivrin calling her journal a Domesday? Sounds more like an accounting ledger. Well, yeah, I guess that’s what Willy Conq’s book was after all, so why not keep that continuity?

I don’t understand why Montoya was present for Kivrin’s drop back into time. I see her purpose for being in the story, but certainly not why she’s there at the start.

Why would something happening to Kivrin in the past be irrevocable? Couldn’t they just go in earlier and collect her? Ah, never mind, it does get explained. Ick.

Oh man, between Gilchrist and Latimer, I’m not sure who I think less of. They don’t really know if Kivrin has made it safely or not and all Latimer can think of is “at last we have the chance to observe the loss of adjectival inflection and the shift to the nominative singular at firsthand”. Gilchrist reminds me of the know-it-alls who base their facts on what they want them to be. He’s been more interested in the anthropological aspect of Kivrin’s drop back in time than in the actual science involved in getting her there.

Nor is he at all, and I do mean at all, concerned about Kivrin. He’ll abandon her at the least sign of it impacting his position badly. He’ll ignore standing operating procedure. He shovels blame at the drop of a hat. He makes me furious!

Wait, if Badri has said the slippage was minimal and then all of a sudden it becomes “minimal slippage” and Dunworthy figures he should have asked about “maximal”…and I’m so confused, again.

It seems as though Oxford has been doing these visits into the past for some time, so wouldn’t they have some ideas about taking something along to use as a marker so the visitor knows where to come back for the return trip? Wouldn’t they have had other drops that don’t go perfectly? Wouldn’t they have prepared Kivrin for initial misadventures? Um, since the 1300s doesn’t have central heating, why shouldn’t Kivrin know how to build a fire? How does Medieval think people kept warm indoors? Since Kivrin knows she shouldn’t be telling the contemps (contemporary people of the time period) about time travel, why is Kivrin talking about her time travels to the people of the fourteenth century?

It starts off confusing, drops into a comedy as Dunworthy fusses worse than an old mum, Gilchrist alternates between pouting and crowing, and poor Kivrin simply wants to fulfill her dreams. Dreams she’s spent two years working toward. And in many respects, it’s Dunworthy who’s to blame for it all. He’s made too many people paranoid.

But then it drops into a parallel tragedy with both sides of the time continuum ill. It may take the 1300s a bit to catch up, but both will need quarantining and lots of care. Events that have a tremendous impact on Dunworthy’s worries about getting Kivrin back, as well as on Kivrin in her understanding of the fourteenth century.

Why are they worried about the spelling of her “name”? Spelling was all over the place at the time. Speaking of names, why do they keep referring to Montoya as Ms. if she’s a professor? Wouldn’t it have been more appropriate to call her doctor or professor?

I love that the bells Kivrin is so used to hearing in 2054 Oxford are mostly here in 1300s Oxford. There’s such a comforting sense of connection in the continuity of the bells having lasted so long and with Kivrin recognizing the voice of each bell. Montoya’s dig at Skendgate is another bit of parallelism, and I keep expecting her to find evidence of Kivrin. It’s enough to keep me on the edge of my seat.

Oh, wow, I think it’s a bit of a stretch, but still, oh wow. It’s fascinating to see how Kivrin pulls fairy tales into the story with “Everywhere I look I see things from fairy tales: Agnes’s red cape and hood, and the rat’s cage, and bowls of porridge, and the village’s huts of straw and sticks that a wolf could blow down…the bell tower looks like the one Rapunzel was imprisoned in” and Rosemund looking like Snow White.

Willis pulls in Jesus several times with an interesting parallel to Dunworthy’s worries about Kivrin. The first time made me laugh.

As an example of what a jerk Gilchrist is: “Death was a common and accepted part of life [in the 1300s], and the contemps were incapable of feeling loss or grief.” W. T. F.

Oh, lord, Mrs. Gaddson cracks me up! I do love how slippery and ingenious Willy is, though. Must have been all the years he spent getting ‘round his mum, LOL. Then there’s that comment about the ancient sister embroidering initials on towels. I can so see that, ROFL.

Why doesn’t Lady Imeyne know the truth?

Frustration, laughter, intrigue, and such sadness. I had to cry, especially when Kivrin wonders: Perhaps that’s what’s wrong with our time, Mr. Dunworthy, it was founded”…by all the nasty people who survived while the ones who stayed and tried to help died. When they come across the horse with its chased bridle…

The Story

It’s a cock-up of major proportions with fear and ambition feeding it all as Dunworthy hasn’t any faith in the other college’s experience in sending Kivrin Engle into the past. For good reason as it appears that the Acting Head has pushed everything too fast and too far simply to make himself look good.

It’s Midnight Mass with Father Roche when Kivrin makes the connection, that contemps are real people.

The Characters

Kivrin Engle is an undergraduate student at Oxford with a fascination for how things worked in medieval England.

James Dunworthy teaches at Balliol and Kivrin is his favorite student. Badri Chaudhuri is a net technician from Balliol college, the best. I think Balliol handles Twentieth Century visits. Finch is Dunworthy’s secretary who obsesses over silly minutiae. Andrews is the closest tech who seems to be available. Polly Wilson is another tech.

Latimer is Kivrin’s tutor. Basingame is the missing head of the History Faculty with Gilchrist (a pompous, self-righteous idiot with excessive ambition) as Acting Head while Basingame has gone off on a fishing holiday. Puhlaski is the apprentice Badri replaces. Lupe Montoya is a visiting American professor of archeology working on a medieval dig. Brasenose college appears to handle Medieval drops; Magdalen works the Renaissance.

Dr. Mary Ahrens is in charge of the Infirmary at the college and Dunworthy’s friend. Colin Templer is Mary’s twelve-year-old great-nephew with a very active role in this story. Deirdre is his irresponsible mother and Mary’s niece.

Ms. Taylor and Helen Piantini, the tenor, are among the bell ringers from the Western States Women’s Guild of Change and Handbell Ringers from Colorado

Mrs. Gaddson, a.k.a., the Gallstone, is an overly religious, helicopter of a mother—think of her as comic relief. So very worried about her very robust son’s health. Willy Gaddson is quite the lady’s man and seems to know a lot of people of whom he can ask favors. Women-type people…snicker…

The People of Skendgate, 1300s

Lady Eilwys is the Lord Guillaume D’lverie‘s lady who is in love with Gawyn, her lord’s privé. Rosemund is her twelve-year-old daughter, betrothed to Sir Bloet whom she will marry this coming Easter. Agnes is her six-year-old daughter who needs the world to revolve around her. Blackie is her new puppy. Maisry is the slow-witted servant girl. Lady Imeyne is Lord Guillaume’s mother who is so obsessed with status.

Father Roche is the village priest and not high-falutin’ enough for Lady Imeyne. The steward and his wife have five children of whom only Walthef, the oldest, and Sibbe and Joan are mentioned by name. Ulric is Hal‘s son. Ulf is the reeve.

Sir Bloet lives at Courcy, and he’s a fifty-something fat man looking forward to wedding twelve-year-old Rosemund. Lady Yvolde is Bloet’s sister, and she’s run his household for years.

The bishop’s envoy, his clerk, and a Cistercian monk come galloping to Skendgate.

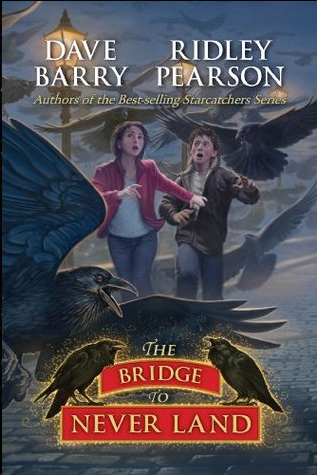

The Cover and Title

The cover has a white background with a blue Celtic border framing the cover and another Celtic motif in a pale grey in the cover’s center. Over it is the book’s title in a red Gothic font.

I should have thought the name of William the Conqueror’s book would have been more appropriate, but then I got to wondering if Willis intended to warn us, that it was indeed a Doomsday Book in light of what happens.