I received this book for free from my own shelves in exchange for an honest review. This does not affect my opinion of the book or the content of my review.

Source: my own shelves

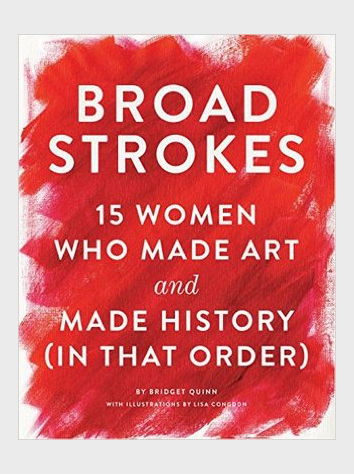

Broad Strokes: 15 Women Who Made Art and Made History (in That Order)

by

Bridget Quinn

biography, non-fiction in a Kindle edition that was published by Chronicle Books LLC on March 7, 2017 and has 192 pages.

Explore it on Goodreads or Amazon

Illustrator: Lisa Congdon

Fifteen mini biographies of women artists through history representing different periods in art.

My Take

Consistently throughout these fifteen biographies, we learn that Quinn had to hunt and search and struggle to find information on these women, of the obstacles, denigration, and deprivation that each woman struggled through.

The “introduction” to Broad Strokes explained how Quinn came to find a need for it. Fascinated by these incredible painters in her art history classes, Quinn began to question where the women artists were. You’d think in our day and age that professors would be pulling them in, providing more of a balance, and taking the opportunity to note the social histories of their times. Instead, as soon as the establishment realizes the painter is a woman, the work is suddenly inferior or she’s sleeping with her models or other artists or a man actually did the painting for which she’s claiming credit? Are men that insecure?

Quinn came to believe that women couldn’t be great artists, especially when Janson’s 800-page book, History of Art, 2nd ed., only noted sixteen women, including Mary Cassatt and Georgia O’Keeffe. Just a few of the women not in Janson’s book included Edmonia Lewis, Frida Kahlo, and Lee Krasner. All had certainly been around long enough to be included!

Quinn weaves in a quick biography of each woman with her own autobiography of where she stood at each stage of her research and has included at least one example of each artist’s paintings as well as a contemporary portrait of her. I very much enjoyed Quinn’s assessment of the paintings. What underlies the painting and how it reflects the culture of the day. As well, Quinn includes a quick biography of the artist’s life, the good and the bad.

A comment Quinn makes in reaction to another artist made sense to me. We’ve all seen art that we know our three-year-old could do, and somehow, the critics believe it’s great for whatever reason. But I like the idea “that a good erotic jolt is appropriate…”

The Artists

The talent of Artemisia Gentileschi (1593–1656) was recognized by her father, Orazio Gentileschi, who was an admirer of Caravaggio, which he taught her.

The work of Judith Leyster (1609–1660) was a shock when the conservation department discovered that a painting by Frans Hal was *omigod* actually painted by a woman. From great rejoicing over having acquired a fabulous painting to total rejection, simply because the painting was done by a woman. As late as 1964, her work was denigrated for “the weakness of the feminine hand”.

A Dutch Golden Age painter, Leyster was of a time when artists no longer had to depend upon the Church or wealthy patrons.

Adélaïde Labille-Guiard (1749–1803) painted textures so beautifully that people commented on “how amazingly like real silk her dress was”, and she managed to force the Academy to recognize her talent through a brilliant stratagem, lol. I love the purpose behind her self-portrait. Another “up yours”, *more laughter*. She managed to survive the French Revolution, partly by burning her most ambitious composition.

I think she’s one of my favorites in this for her intelligence, ability, and the romance.

Élisabeth Vigée-Lebrun (1755–1842) was a famous portrait painter and was considered a rival of Adélaïde’s. While the men put down her work, she was court painter to Marie Antoinette.

Marie-Denise Villers (1744–1822) was a French Neoclassicist who specialized in portraits. She “returned” to fame when the Met thought they were getting a Jacques Louis David painting, Portrait of Charlotte du Val d’Ognes, a landmark work. That turned out to be painted by a woman. Popular with the public, the “establishment” suddenly found reasons why it was so bad.

Villers’ bio includes a condemnation of Napoleon for shutting down education and exhibitions for women artists, which lasted way too long.

Rosa Bonheur (1822–1899) was known for her “big and muscular and naturalistic art” — particularly animals, her preference for women, and being an avid hunter and horsewoman. Her section includes a gorgeous portrait of Buffalo Bill Cody and her painting Ploughing in the Nevernais looks like a photograph. She and her three sisters all became renowned artists. Hmmm, she also needed a license for cross-dressing…I told’ja we learn about the culture of their times, lol.

Edmonia “Wildfire” Lewis (d.1907) was a nineteenth century Neoclassicist sculptor born of a Chippewa woman and a Black. It was hard enough to be a woman artist, but adding in her ethnicity made it harder. She states “The land of liberty had no room for a colored sculptor.” I did enjoy Quinn’s comment in reaction to pejoratives from Henry James that white marble was the medium in which fine artists work. That it was not a self-hating message. She goes on to note that Caucasians aren’t white either, and it’s why sculpture was always painted in the ancient world. So take that, James.

Born 1876 and died 1907, Paula Modersohn-Becker‘s oeuvre was German Expressionism, and “her work was among the first of … German modernism”. If she hadn’t persevered and escaped her father for an artists’ colony, she would have lived and ended her life as a governess.

Vanessa Bell (1879–1961), Virginia Woolf’s sister, was part of the Bloomsbury Group and caught up in paintings of daily life — and the opposite of her sister in confidence.

Alice Neel (1901–1984) is considered the greatest American portraitist of the twentieth century, but almost missed living long enough to create. Suicidal and raving, she was forbidden to draw or make art. That’d be enough to drive me bonkers! She certainly was a free-living woman who stuck to her guns!

Lee Krasner (1908–1984), an abstract expressionist, discovered Jackson Pollock and eventually married him. She was the more famous of the two at the start, and “so accomplished that her instructor, Hans Hofmann, paid her the ultimate compliment: ‘This is so good you would not know it was painted by a woman.”

Excuse me? And it’s an attitude that prevails with most women artists. How sad.

I appreciated Quinn’s defense of abstract art and understand it much better…but I’ll never be able to accomplish it.

Louise Bourgeois (1911–2010), becoming an artist in spite of her father, was a Surrealist sculptor and painter who also created installation art.

Ruth Asawa (1926–2013), a victim of the Japanese internment camps during World War II, was known for her wire sculptures and activism. And her sculpture are gorgeous!

Ana Mendieta (b.1948, murdered 1985) was a Cuban American artist most known for her performance art, earthworks, and portraits-cum-crime-scene-outlines, creating a “new and powerful art form”, inspired by the racism she and her sister were exposed to in Iowa.

Kara Walker (1969– ), the daughter of an artist, is a Black contemporary painter, silhouettist, and installation artist who is comfortable poking at race, gender, sexuality, violence, and identity in her work.

I do like the concept of her mammy sphinx *grin*. Walker is quite accepting of the negatives people say about her work: “People respond … in the way that they do. It’s not unexpected.”

Susan O’Malley (1976–2015) was a text-based artist whose mother’s condition focused her into her art, fascinated by how we live. She sounds like she was a beautiful woman who shared with everyone.

And don’t forget: “Art Before Dishes”. Now that I can get into, lol.

The Cover and Title

The cover has a white background with broad brushstrokes of red as a backdrop for the white text, the title taking up most of the cover with the author’s name quite tiny below it. The illustrator’s name is even tinier under that.

The title is what we get, Broad Strokes: 15 Women Who Made Art and Made History (in That Order), as Quinn realizes how little is known about women artists famous in their day.